Adaora Igonoh, M.D., is a general practitioner in Nigeria who contracted Ebola this past summer while treating a patient who ultimately died from the virus. She was ill for 17 days and spent 14 days in a hospital isolation unit before she was declared Ebola-free and released. She's gone back to treating patients now and recently spoke to Cosmopolitan.com about her experience and recovery.

I contracted Ebola in July from Patrick Sawyer, a patient who was admitted to our hospital. He had a fever but said he hadn't had contact with any Ebola patients or attended a funeral of someone who died of it, which is how people usually get sick. We thought he just had malaria, which is so common in Nigeria that anti-malaria medication is available over the counter.

I was one of the doctors who actually treated him. We went into his room every morning for rounds. The day after he was admitted, I was the one on duty when he called the nurses' station asking for a doctor. He was on his bed with his IV bag right beside him, and he said he wanted to use the restroom, although he'd already gone about five times that day. Before I went to get a nurse to help him, I picked up the IV bag with my bare hands and placed it back on the stand. The bag didn't feel wet or sticky, but he must have vomited or had diarrhea and touched it. I washed my hands directly after that, but anything could have happened between leaving the room and washing my hands at the sink, like touching my face with my hands.

He wasn't getting any better, so after 48 hours, we suspected he might actually have Ebola. The blood tests came out positive, and he died the following day. I was the one who was beside him, fully protected with gloves at that time.

When we found out the patient had died of Ebola, everybody in the hospital was filled with anxiety and tension and panic about getting it, which was a real possibility for me because I was around him. After he died, every single person who had treated him was told to go home, all the other patients were discharged immediately, and the hospital was sealed for decontamination. We were instructed to have our temperatures taken twice per day and fill out a temperature chart. Before you develop symptoms, it's almost like you're just waiting for a cold or someone to confirm that you actually have the virus.

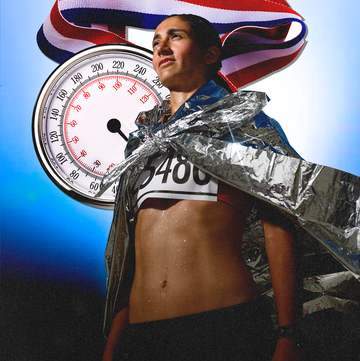

We were told that the first symptom would be a fever, but the first symptom is actually joint pain, especially at the knees and the ankles, and body aches. You feel like you walked a mile when you actually haven't done anything. I thought that maybe it was the stress of everything that had gone on. And as soon as I recorded my first fever, I thought, This can't be possible. So the next day I checked again, and it was actually a fever. I thought maybe it was malaria, because it usually begins with joint paints and body aches, and morphs into a fever. But I took an anti-malaria pill and still wasn't feeling better. At that point, I decided to advise the authorities that I had a fever and provide blood samples for investigation. Thank god I didn't pass the infection on to anyone.

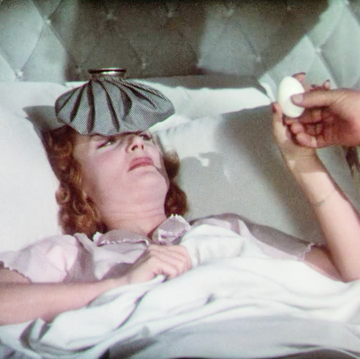

On the second day of my fever, I started to get diarrhea and I started vomiting. I was already weak at that point, and I was taken to the isolation ward of the hospital. I can't really explain my state of mind at that time. I was just hoping and praying that it wasn't Ebola, but I knew I couldn't rule out the possibility. I was faced with the reality that I could have the disease that has killed literally hundreds of people in Liberia, Guinea, and Nigeria, that has no cure, no vaccine, no treatment, and a mortality rate between 50 and 90 percent — that's a 10 percent rate of survival.

When I got there, I was given instructions to drink lots of fluids, even though I didn't feel like I had the strength to drink. When you vomit and have diarrhea at the same time, you lose a lot of fluids. The number one cause of death in people with Ebola is the shock of dehydration.

When you have Ebola, you can't count how many times you've thrown up — maybe every hour, although some people have more diarrhea and throw up less. It's really a lot during the first few days. There's a greater chance of survival if you actually get to the hospital, where you can replace the fluids you've lost. Your eyes get sensitive to light, and you get sores in your mouth that make it difficult and painful to swallow and eat, even though you need the fuel to keep up your strength. Ebola gets into the cells and sort of just replicates and multiplies and attacks the cells. And because the virus targets the organ that produces blood clotting, there can also be bleeding from different orifices, internally and externally, and it eventually causes death.

You need hope. The only thing that gave me that kind of hope is faith and the belief that God is able to heal all. People said prayers for me to survive, and that gave me the strength and the willpower to drink and hydrate and rehydrate.

There were four other women in my isolation unit. I was the only doctor there, with two other infected nurses, so I had the responsibility of being the patient-doctor in the ward. One of the women had a fluid IV because she couldn't tolerate water and was too weak to drink. It was challenging for doctors to come into the room often because of the complicated protective procedures, and because it's stressful for doctors to take care of Ebola patients. Often, I had to change her fluids because if I didn't, no one would. Survival often depends on the human resources that are available. People are at different stages of sickness severity and recovery in the isolation ward, but I don't know if it's common for recovering patients to help weaker patients. In some cases, people are scared of helping other patients because they are afraid they are going to be reinfected. I haven't heard of or read about any cases of a patient being reinfected.

We had to encourage each other, because it was so depressing. I was in the isolation unit for 14 days. We didn't have a TV, but we had some books and my pastor sent a CD player. We were able to communicate with our family members and friends. But when you're in isolation, you don't really want to communicate with anybody at all — not everybody can handle the fact that you have Ebola. I had my iPad so I could always browse the Internet, or go on Twitter or YouTube. But you really don't care about entertainment. You just want to get better and get stronger.

We told each other that we're not going to die here, we're going to live. If you believe that in your heart, it gives you the hope and the faith to actually survive. That's how people come out of it, although two of the women — including the nurse I helped — actually died from the disease.

I think recovery — which is mental and physical — actually starts when you leave the isolation ward. Joint pain lingers even after you're cured of the virus. When you get home, you have to eat well and sleep well and recover the weight that you've lost. It can take weeks and months to regain your strength.

The only people who knew that I had the infection at the time I left the ward were my family members and my pastor. I didn't tell anybody until I started talking to the media about how I survived the infection. Some people doubted that I was completely cured. There will always be naysayers. Even well-educated people — even doctors — still stigmatize people who've had the infection. People fear what they don't understand, and Ebola is not fully understood. For instance, people are skeptical about the mode of transmission. There are quite a number of people who feel like it's airborne, that you can actually breathe it in [which is not true].

Having Ebola gave me an insider perspective on the disease. It just gives me a better understanding of everything the patient is going through and how badly they need to be reassured that Ebola is not a death sentence.

Nigeria is Ebola-free, but it's important not to panic in places like New York City where there are confirmed cases. Ebola is preventable by washing your hands regularly and not touching people who are sick. Once you panic, you start to act irrational (i.e., there's no need to wear a full face mask to the airport) when you really need to be clear-headed and rational and spread hope instead of fear. If you suspect somebody has been in contact with an Ebola patient and is beginning to exhibit symptoms such as fever, vomiting, and diarrhea, you don't go touching the person. Notify a health authority on behalf of that person.

Irrational fear can end up affecting your body. Before I developed Ebola symptoms, I actually went to the restroom five times out of anxiety — that can make you sick. You don't want to be sick just from fear. Ebola is not a death sentence.

Follow Elizabeth on Twitter.

Elizabeth Narins is a Brooklyn, NY-based writer and a former senior editor at Cosmopolitan.com, where she wrote about fitness, health, and more. Follow her at @ejnarins.