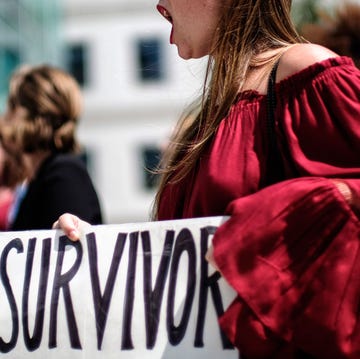

With 1 in 5 women sexually assaulted while in college, sexual violence is an endemic campus problem. But schools and universities still vary widely in how they handle it, with some owning the issue and working to keep students safe while others simply go into risk management mode or deny they have a problem at all. So how do you know if your school has good sexual assault policies?

Cosmopolitan.com talked to leading experts on campus sexual assault about what a comprehensive policy looks like, red flags to watch out for, and what you can do to improve the policies on your own campus.

1. Is information easy to find?

If a school is truly dedicated to preventing sexual assault, holding perpetrators accountable, and supporting survivors, the proof will be on their website and in the student handbook. "Look for schools that have clear policies," saysJaclyn Friedman, sexual assault educator and author of What You Really Really Want: The Smart Girl's Shame-Free Guide to Sex and Safety. "It shouldn't be written in bureaucratic-ese."

If you're not able to get answers to your questions, either through the school's website or by asking the appropriate administrator, that's cause for concern.

2. Does the school admit it has a problem?

"The No. 1 red flag is a school that says, 'We don't have a problem with sexual assault,'" Friedman says. "A school that says they have no reports is sweeping it under the rug. They are deeply in denial and are not going to handle it well. A school that says, 'Yes, we have a problem, and here's what we are going to do to work on it' is a school that is going to engage with you."

It might sound counterintuitive, but a high number of reports doesn't necessarily mean a higher number of assaults — it might mean a higher number of students who feel safe coming forward. "A big red flag would be looking at a school that only has two reports or a very small number in relationship to the size of the school," says Nancy Schwartzman, CEO of Tech 4 Good, the company behind the Circle of 6 app, which helps prevent sexual assault by privately connecting users with a close network of friends. "That says students don't feel safe reporting, they don't know where to report, they don't know they have the option to report, and they don't know there are survivor services on campus."

3. How does the school define "consent"?

First, your school should make it easy to figure out how they define sexual consent. And they should have a model of "affirmative consent," or "yes means yes" — that is, both parties have to affirmatively want to have sex and must express that desire, rather defining consent as not saying no.

"A school that has adopted an affirmative consent standard is more likely to understand that sex should be an act of joy for everyone involved and that all of their students are sexual agents," says Alexandra Brodsky, co-founder and director of Know Your IX, an organization that combats sexual assault and educates students on their rights under Title IX. "Not all survivors are women but most are, and schools that have other standards are seeing their female students as gatekeepers to sex who sometimes regret making the wrong decision, as opposed to sexually autonomous people who have preferences and desires, and sometimes that desire is not to have sex."

4. Can students report assaults anonymously?

"Anonymous reporting is a crucial option," says Wagatwe Wanjuki, a feminist writer and anti-sexual-violence activist. "Students should be able to report anonymously online and should be able to access different resources, like health care services you might need afterward, without having to name their assailant and without mandating referrals to the police. We need to honor the choices of survivors."

Anonymous reporting allows survivors to get the help they need and enables schools to gather statistics on campus sexual assault without forcing victims, who may already feel a loss of control over their own bodies, to feel further disempowered. And if anonymous reports include names of alleged assailants, schools can collect information on perpetrators as well — most sexual assailants commit their crimes repeatedly against many victims, and if a school allows anonymous reporting, it can identify patterns and serial offenders.

5. Is there transparency about the judicial process?

"Make sure it's easy to find out what the judicial process is," Friedman says. "Make sure there's transparency about how it works and that there are advocates available for victims who want to press charges. You also want to look at outcomes: How many cases have been brought, and how many of those people were found responsible? Then, are they expelled, or are they told, for example, to write an apology letter?"

Schools don't always release statistics on outcomes, but if you ask the administration, someone should give you answers. They should also be able to tell you more about victims' advocates — a person to informally represent a survivor in a disciplinary process — and tell you whether they'll allow you to have an advocate from a local organization or a lawyer present with you to help defend your rights.

The judicial process should be clear and easily available online. You should be able to find out the evidentiary standard the school uses (see No. 7), who's on the disciplinary panel, potential consequences for perpetrators who are found responsible, privacy rules, whether you can have an advocate with you at a hearing, and whether you have to face the alleged assailant. Panelists should be trained in handling sexual assault complaints, and the school should take steps to make sure the panel is as impartial as possible.

"A really good practice is to make sure the people on the panel who are deciding the case are not affiliated with the school that both the accuser and the person accused are in," Wanjuki says. "So if you're in Arts and Science, the panel will include a dean from Engineering or Dentistry. It removes potential conflicts of interest, and you don't have to work with a person who heard the most intimate details of your rape."

Both sides should also have the chance to appeal, Wanjuki says — some schools only allow the accused assailant that right.

6. Are sexual assault survivors held responsible for violating student conduct codes?

"It's a total myth that the average campus rape is the drunk girl at the party. But in college, there's a lot of drinking and drug use, and there may have been alcohol and drugs involved in the evening, even if they weren't key to the violence itself," Brodsky says. "So a survivor who had been drinking might be afraid to report to his or her school because they're worried they would be punished for breaking school rules for drinking underage. There are some schools that have made explicit, 'We promise you won't get in trouble for drinking,' and that can be key."

7. What evidentiary standard does the school use for sexual assault?

When a student reports a sexual assault to his or her school, if the alleged assailant is another student, the school will often bring the accused before a disciplinary panel to investigate the facts and decide if he or she has violated campus policy. But different schools have different standards when it comes to what evidence they need to take action against an alleged perpetrator. The criminal justice system uses a "guilt beyond a reasonable doubt" standard — this evidentiary standard is a high one because the punishment for committing a crime is often loss of liberty at the hands of the state. Schools don't have the power to incarcerate but they still have an obligation to protect the rest of their students, so they use a variety of other standards. Some rely on a "preponderance of the evidence" standard, which is also used in civil cases and essentially means that the evidence must indicate that an accused student is more likely guilty than not before he or she will face disciplinary measures. Others use a "clear and convincing" standard, which is a lower bar than "beyond a reasonable doubt" but higher than "preponderance of the evidence." That means a disciplinary panel won't just look at an alleged survivor's version of events and the evidence he or she presents, compare them with the accused and the evidence he or she presents, and conclude that the evidence points in favor of one or the other; the survivor will have to present substantially convincing evidence leaving little doubt that the accused committed an assault. That's a very tough standard to meet without law enforcement and police investigation tools.

"Schools should be using the 'preponderance of the evidence' standard and not the 'clear and convincing' standard," Brodsky says. "The preponderance standard really means putting the survivor and the accused students on an equal playing field, which is not what the criminal justice system does for good reason."

Under the preponderance of the evidence standard, a disciplinary panel in theory only needs more than 50 percent of the evidence to point to a party's responsibility in order to hold them accountable. That means a victim (or a school) doesn't need to show overwhelmingly that an alleged assailant is guilty — just that it's more likely than not he did the thing of which he is accused.

If your school is cagey about which standard they use — or if they use a "beyond a reasonable doubt" standard — that's a big red flag. They should also be clear on what kind of evidence they allow to be presented during the investigation. According to Brodsky, some schools won't allow victims to introduce rape kits as evidence. And, adds Wanjuki, "Schools should follow rape shield law protocol [saying a victim's sexual history cannot be used against her in court], so a victim's past sexual behavior should not be brought up [in a disciplinary hearing]."

8. Is there a preferred sanction of expulsion for sexual offenders?

Punishments for sexual assault vary depending on the school and the type of assault. Some schools level remarkably light penalties for sexual assault — making the assailant write an apology letter or leveling a summer suspension. Some schools also defer to the assault survivor when it comes to punishment, giving her a set of options and letting her pick what she thinks is fair. While some flexibility is key, making the survivor responsible for the punishment can make her feel guilty or pressured into leniency. Some schools strike a balance between flexibility and appropriate punishment by erring on the side of expulsion but not mandating it — that way, if a survivor is adamant that she won't report if the person she's accusing will be expelled, the school can work with her to make sure she gets justice and a perpetrator is held accountable.

"A preferred sanction of expulsion for sexual violence is really important," Brodsky says. "That's not an automatic sanction, because automatic sanctions can actually discourage people from coming forward. But it's a problem when schools put the onus of picking the punishment on the survivor, particularly because most survivors knew the person who assaulted them. There's an expectation of feminine forgiveness that comes into play there. But it's important that if a survivor says, 'I won't go forward with this if I know my ex-boyfriend is going to be expelled,' it's important to respect that. At the same time, a school should want to get a rapist off of the campus."

You should also compare the sanctions for sexual assault to consequences for other violations the school handles. "At some schools, you get a harsher penalty for stealing a laptop than for raping another student," Wanjuki says. "That's ridiculous. If your school's code of conduct makes cheating on a test or stealing more egregious than raping another student, that school needs to reevaluate its values."

9. Do withdrawals while cases are pending go on an accused offender's transcript?

"What sometimes happens when a perpetrator realizes the hearing is not going in his or her favor is that the student will withdraw, and the hearing is put on hold, and then they try to transfer to another school or come back in another year when the victim isn't on campus and the hearing goes away," Brodsky says. "I know one school is putting policy into place that says if you withdraw while you have a pending case against you, that goes on your transcript. That will be a warning that you were trying to duck your responsibility in this case. That's important for practical reasons because it makes it less easy for the rapist to come back to campus, but it also speaks to a school's general concern for keeping future students safe as opposed to just keeping the ones who have been assaulted quiet."

10. Does the school enforce no-contact orders?

Under Title IX, "Schools are supposed to offer no-contact orders, which are essentially a version of a civil protective order, that says your assailant can't live in the same dorm as you or be in the same class as you," Brodsky says. "Some schools are really reluctant to enforce the orders, which makes them toothless."

Schools sometimes don't enforce no-contact orders because it requires them to dedicate resources to curbing an alleged perpetrator from contacting someone he's accused of assaulting, or it means changing his housing, or reprimanding him or even a third party for communicating a message to an alleged victim. Many schools will comply with the letter, though not with the full meaning, of the law: They'll issue the no-contact orders but won't make sure they actually prevent an accused party from contacting or even harassing an accuser, and won't take proactive steps to make sure an alleged victim is protected.

Information on enforcement of no-contact orders, unfortunately, isn't quite as easy to find. But you can and should ask. "A school is unlikely to say on their website, 'We're bad on sexual assault,'" Brodsky says. "This is where students really need to press their administration. Say, 'I see on your website that you enforce no-contact orders. What have you done in the past to enforce them?' Schools often hide behind privacy concerns, but schools are 100 percent able to report information about an event if they remove identifying student information. Student should be able to see how their school is responding to different types of violence."

11. Can survivors receive necessary accommodations?

Sexual assault can lead to depression, anxiety, and PTSD, with PTSD particularly triggered by sensory experiences — a smell, a sound, a place. And the aftermath of an assault may mean survivors miss class, zone out during lectures, miss deadlines, and have a hard time focusing on schoolwork, all of which can impact their grades and make them more likely to suffer academically or leave campus all together. Survivors often need both physical and academic accommodations to make sure they are able to deal with a traumatic event and still remain on campus.

"A good policy has accommodations for survivors," Wanjuki says. "Not just housing accommodations, if their assailant is in the same dorm or they were assaulted in their room and want to change, but also academic accommodations, including allowing survivors to drop classes or get extensions."

12. What is the school's sexual assault prevention program?

Schwartzman recommends looking at what schools think counts as "prevention." Too many institutions think prevention means women should protect themselves, rather than educating the entire community on everyone's responsibility to prevent violence.

"If a school thinks having blue safety lights on campus and having a police presence is enough around issues of sexual assault, they are sorely mistaken and outdated," Schwartzman says. "What is their prevention mandate? Is it, 'Girls, cover your drinks when you go out,' or is it really in-depth about how young men need to respect consent and understand boundaries and lines?"

You also want to be sure your school is offering comprehensive prevention education for all four years and that at least some of it is mandatory for all students, staff, and faculty — the majority of students committing assaults are not incoming freshman, and they need to be reached. And the education should be inclusive, recognizing that not all victims are female and not all assailants are male, and that students in various minority groups may feel different kinds of pressure not to report an assault.

"I want to know what kind of programming is in place and how many staff members are at a school to focus on student safety and wellness," Schwartzman says. "Is there a women's center and an LGBT center? If you're a queer student, is there even language for you around assault as a queer or trans person?"

13. Does the school have an inclusive bystander intervention program, and does it talk about power imbalances?

Bystander intervention programs, which train community members to safely step in to stop perpetrators from honing in on their victims, are increasingly understood as effective sexual assault prevention. Your school should be investing in them. But just using the term "bystander intervention" isn't enough. Programs should address all kinds of sexual violence and talk about gender roles, power dynamics within relationships and communities, and masculinity.

Brodsky says some schools are treating bystander intervention as a "silver bullet" and are "throwing money into it as an attempt to perform their concerns," even though some programs can be too limited in scope, and some fail to address the root causes of sexual violence.

"Some bystander intervention models are focused on only one narrative of violence that's not the most frequent type – 'There's a drunk girl at a party and there's a guy trying to take advantage of her and you're supposed to step in,'" she says. "That's a good thing to do, but you also have to be able to recognize signs of an abusive relationship and connect her safely to mental health resources. We have to recognize violence happens between two men, between two women, and we also need a longer-term picture of how violence developed and all of the points at which we have to intervene."

14. Who receives training on sexual violence, and what are their obligations?

Colleges and universities should have a stable of individuals on campus who are trained in dealing with sexual assault, survivor services, and compliance with federal law. That includes mental health professionals, a Title IX coordinator, student leaders, faculty members, Greek life representatives, resident advisors, and other staff. If your school has only one person responsible for all the sexual assault issues on campus, that's a problem. And the school should be clear on the obligations of anyone to whom you report an assault — some people are "mandated reporters," meaning they have to report the assault to law enforcement. Others will have to report to your administration. That means that if you're assaulted and you go to an RA, a professor, a student educator, or an administrator, they may be required to report your assault to the administration, whether you want to report or not (they may even have to report it to the police). That lack of control over how and to whom to report can be devastating to victims who have just had control of their own body violated by an assailant. A school with a good sexual assault policy will try to put as much of that control back in the hands of survivors — and that means being very clear on who a survivor can speak to in full confidence.

"Ask what kind of training are resident advisors getting on this issue," Schwartzman says. "That's one of the first people you go to [if you're assaulted]. If you report to an RA, are they mandated to tell the police?"

The school has quite a bit of flexibility in determining who has to report and who can keep your story confidential, so roles vary widely between campuses. A school with a good sexual assault policy will make reporting requirements crystal clear.

15. Does the school inform students of their rights?

"We sometimes get emails or pictures from administrators at schools that have used Know Your IX materials," Brodsky says. "When you have a school that says, 'You should know you could sue us,' that's a pretty good sign."

If you can't find information about how the school complies with its Title IX obligations, ask. And if administrators aren't forthcoming, take that as a bad sign.

16. What are the services available for survivors?

"I think of college campus approaches to sexual violence as having three pillars: prevention, justice, and support for survivors and healing," Friedman says. "How are the mental health services? Are there trained counselors specializing in helping survivors? What are students' experiences with the mental health counselors? When I went to the head of mental health when I was an undergrad on campus, she encouraged me to forgive my rapist, and I had to go out of pocket to find someone off campus."

Ask how many mental health counselors are trained in helping assault victims and what services students are entitled to. Is there a cap on the number of mental health visits a student gets? What does the school insurance cover, and what's covered if you're on your parents' insurance, otherwise insured, or not insured at all? Does the school's website offer other options, including confidential hotlines and local survivor services? Does the school help connect students with off-campus resources?

17. Do students have a real voice in the process, and who are those students?

"The administration shouldn't be making decision in a vacuum," Friedman says. "There are very few schools I've been to where the students say, 'We really feel like the administration has our back.' But if you find a campus where the student activists say, 'The administration is on the same page as us and we're working together,' that's gold."

And it's important that the school engages the right students, Brodsky says. "They should be talking to survivors groups and women's centers and anti-violence associations, and not just the student body president."

On some campuses, Friedman says, the administration requires Greek life leaders to come to sexual assault prevention talks and does pre- and post-testing to make sure they understand the issues; then the administration relies on those students as leaders. And in planning programming around prevention as well as disciplinary procedures and survivor support, talking to feminist leaders and sexual assault survivors is key.

18. Are there activists on campus, and what do they say?

Other students are your best resource. When you visit a school, see if you can set up a chat with members of the on-campus women's organization and ask them about sexual assault on campus and how the administration handles the issue. "Don't just ask the tour guide and the admissions counselor," Friedman says. "If there are no student activists working on this issue on campus, that's also a red flag — it means it's a community that is really not grappling with the issue."

Finally, be an advocate for yourself and know the resources you have at your disposal. In April, the Obama administration issued its task force report on sexual assault on campus, and more recently unveiled NotAlone.gov, a comprehensive resource that helps survivors find crisis centers, lists students' rights and the school's responsibilities under Title IX law, and offers information on how to file a Title IX complaint against a school. Their resource page offers a long list of options, including a map where you can plug in your zip code and see resources near you.

Brodsky's Know Your IX works with students so they can learn about their rights under Title IX. Schwartzman's Circle of 6 App is increasingly being adopted by college campuses; Friedman does on-campus talks and trainings on affirmative consent and sexual violence. SAFER is run for and by college students to advocate for better sexual assault policies. Other resources include The Green Dot, which focuses on violence prevention; RAINN, which operates a confidential sexual violence hotline and can help connect survivors with local resources; and the National Organization of Sisters of Color Ending Sexual Assault, which supports and advocates for survivors of color.

Sexual assault is a widespread problem, and colleges should be doing everything they can to keep students safe and remove predators from campus. A transparent, comprehensive policy that addresses all the above questions doesn't guarantee safety on campus or a fully enlightened administration and student body, but it's a pretty good step toward the ideal.

Follow Jill on Twitter.

Jill Filipovic is a contributing writer for cosmopolitan.com. She is the author of OK Boomer, Let's Talk: How My Generation Got Left Behind and The H-Spot: The Feminist Pursuit of Happiness. A weekly CNN columnist and a contributing writer for the New York Times, she is also a lawyer.