When my gynecologist said I needed to go on birth control pills at age 14, my feminist mother rejoiced. I'd been missing several days of school every month since my period had started two years earlier, bringing with it vomiting, mind-numbing cramps, and the kind of heavy bleeding that ruins white jeans and fragile middle-school egos.

"Thank God for the Pill," my mom said. "Now you won't have to suffer like I did." She came of age pre-Advil and spent the first three days of her period cradling a hot-water bottle and throwing up everything she ate. My grandmother had even more dire stories about surviving as a teenage girl in World War II England (that would be before Advil or Ultra Thin Maxipads). The menstrual cycles of the Sole women have always been violent and all-consuming, but at last, liberation was at hand.

So I kept my pack of Ortho Cyclen tablets next to my toothbrush and faithfully popped one at the same time each night. My cramps and nausea eased within a few cycles. While other girls were getting caught off guard by irregular periods that seemed to show up right before a trip to the beach, I knew almost to the hour when mine would start and stop. I also neatly sidestepped the angst of teenage acne, and when I started having sex a few years later, I had my contraception covered. Taking the Pill made me feel in control of my body and my choices. It was everything feminists had fought for, all wrapped up in a purple plastic packet.

I wasn't the only woman being prescribed the pill for so-called off-label reasons—meaning any reason other than pregnancy prevention. More than 80 percent of sexually active U.S. women will use the Pill at some point during their lives, the CDC reports. And, according to a 2011 Guttmacher Institute report, an estimated 58 percent of women currently taking hormonal contraceptives say they're not doing so to prevent pregnancy, or at least not only for that. Thirty-one percent use it to control cramps, 28 percent to regulate their cycles, and 14 percent to treat acne. In fact, 14 percent of current Pill users cite one of these purposes as their sole motivation.

The Pill has become not just a cure-all for "female troubles" but also a stand-in for reproductive rights. When Rush Limbaugh and his conservative brethren were attacking women's access to the Pill through Obamacare, we all understood it to be an attack on women's rights. And this made me feel like a bad feminist when—14 years after I popped my first one—I began to have doubts about whether the Pill was the silver bullet I'd initially thought.

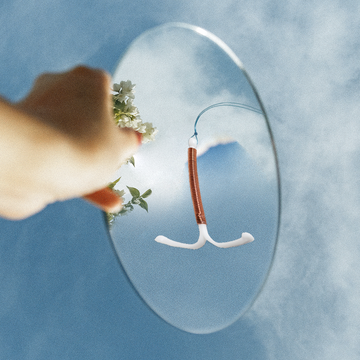

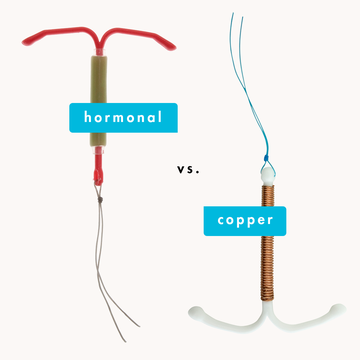

At 28, bedeviled by side effects such as sore breasts, loss of libido, and migraines, I took my doctor's suggestion that I stop taking the pill. I had an IUD inserted instead. "Your cycle has been suppressed almost since you started having one," my doctor noted. "Let's see how you do if your body gets back in the driver's seat."

As it turns out, my body is a crap driver. While my sex drive did bounce back, the intense cramping and bleeding returned too. I developed an ovarian cyst that ruptured, producing a stabbing sensation that made regular cramps feel like warm hugs. In 2012, a month after my thirty-first birthday, I had surgery to diagnose and remove endometriosis.

Endometriosis is a chronic condition in which excessive estrogen causes the uterine lining that is normally sloughed off during your period to build up and grow in places it shouldn't, forming painful cysts and lesions on other reproductive organs. In the most severe cases, this rogue tissue can bind organs together or spread beyond the pelvis altogether, to the lungs and eyes. It afflicts as much as 10 percent of women of reproductive age, and between 30 and 50 percent of them are infertile. And it's a slow burn—as I soon learned, the average time between onset to diagnosis is 11 years. "Well, I guess I got lucky because I got diagnosed so quickly," I said to my surgeon.

"Actually, I think you waited a lot longer," he replied. "Most women with endometriosis report heavy periods and intense cramping in their early teenage years—but we put them on the Pill right away, so we never know they have the disease." Indeed, one recent study published in the journal Fertility and Sterility confirms that women with moderate to severe endometriosis are four times more likely to have been prescribed the Pill before age 18 to treat menstrual pain. Even when endometriosis is suspected (it can be formally diagnosed only via surgery), the Pill is the most commonly prescribed treatment; doctors typically consider surgery or more aggressive drugs (which put you into a false menopause) only for women who can't find a version of the Pill that stops the pain.

Most versions of the Pill work by releasing a steady dose of synthetic progestin and estrogen throughout the month. These formulations squelch the production of the body's own reproductive hormones, and without the signals from the naturally made hormones, the ovaries don't release eggs, thus preventing pregnancy. But in the process, the Pill spurs dozens of other physical changes, which is why it's become the first, and often only, line of attack to treat a raft of female troubles—whether serious medical conditions like endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome (both of which can cause infertility and other complications) or more mild complaints such as acne, mood swings, PMS, or bloating. "The Pill has become the major nonsurgical tool of gynecology," says Jerilynn Prior, MD, professor of endocrinology and metabolism at the University of British Columbia and founder and scientific director of the university's Centre for Menstrual Cycle and Ovulation Research.

Whether that's a positive or a negative depends on your perspective. To Christiane Northrup, MD, author of Women's Bodies, Women's Wisdom, prescribing the Pill for debilitating menstrual conditions, such as the endometriosis I suffered from, only masks the problem. "It's like a mechanic putting a piece of duct tape over the indicator light on your dashboard and claiming he's fixed your car," she says.

But to mask endometriosis is also to slow its course, and to believers in the Pill, which includes most of the gynecological establishment, so-called menstrual regulation has been a huge boon for women's health and personal freedom. "I've been in practice for 24 years, and this is always something we've done," notes Jeanne Conry, MD, president of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).

Granted, she says, the situation became more complicated when the FDA began in the mid-2000s to let Pill manufacturers tout what for decades had been off-label uses. There was Duramed Pharmaceuticals' Seasonique, which would allow women to "repunctuate" their lives by having just four periods a year, because "when you're on a birth control pill, there's no medical need to have a period." Then came the blockbuster drug Yaz, from Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. Marketed as "beyond birth control"—with ads featuring the catchy tunes "Goodbye to You" and "We're Not Gonna Take it"—Yaz promised to alleviate acne, weight gain, mood swings, and menstrual headaches, owing to its low dose of estrogen and new form of progestin. It quickly became the country's best-selling hormonal contraceptive, with annual sales of more than $1 billion. The problem was, while all hormonal contraceptives can cause blood clots—about two cases per 10,000 women, but higher for those over 35 or who smoke or suffer from aura migraines—the FDA began receiving reports in 2009 that seemed to link Yaz to a higher incidence of the potentially fatal condition.

As a result, the agency requested that Bayer launch a $20 million ad campaign to set the record straight, but decided not to pull Yaz from the market when research, funded by the company, concluded that it carried no higher risk for blood clots than competing birth control pills. (Other reports have since put the clot risk for those who take Yaz as high as 10 cases per 10,000.) And an ACOG Committee Opinion published last year essentially affirmed the FDA's opinion, stating that women who don't have particular risk factors for clots can stay on Yaz.

So for most gynecologists, it's business as usual for the Pill, leavened with a dash of caution regarding Yaz. "I have taken most of my patients off Yaz because there are so many other options out there," says ACOG president Conry.

It's this strategy of switching Pills—rather than rethinking the readiness with which they're prescribed—that drives critics like Northrup and Los Angeles journalist Holly Grigg-Spall crazy. At 30, Grigg-Spall told her ob-gyn, a woman, that she planned to quit Yasmin (which is similar to Yaz but has a higher estrogen level) because she feared it had something to do with her depression, migraines, and insulin resistance, among other things. Her doctor didn't quibble with her decision—in fact, she said, "I'm not surprised; the Pill made me feel depressed for years until I came off it"—and then immediately suggested an alternative brand. The author of last month's Sweetening the Pill or How We Got Hooked on Hormonal Birth Control, Grigg-Spall took the newly prescribed Pill for six months, she says, but her depression didn't lift until she quit using hormonal contraceptives altogether.

There is a decent amount of data to buttress anecdotal reports like Grigg-Spall's, including a recent study out of Australia that garnered headlines with its conclusion that women on the Pill were twice as likely to experience depression, anxiety, mental numbness, and an inability to feel pleasure from normal activities (known as anhedonia). These kinds of side effects can be among the most frustrating because they're so easily dismissed by doctors and even by the women experiencing them. "I kept thinking, Oh I'm just stressed out," says Grigg-Spall. "Then after awhile, you start to think, Maybe this is normal for me. It's hard to connect it to your birth control."

The confusing upshot is that some women take the Pill precisely because they say it stabilizes their moods, while others say it disrupts theirs. To add one more perplexing twist, Gillian Einstein, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of Toronto who studies the biochemical effects of hormones on the brain and cognition, says that when her lab measured women's hormone levels, they found no correlation between subjects' menstrual cycles and mood in the first place. "And yet, we have entire industries built around the idea that women are moody and irrational before their periods," Einstein says, suggesting that the idea that menstruation messes with women's heads may be driven more by a culture that makes it difficult for them to express anger than by their biochemistry.

As for whether the Pill itself influences women's emotional equilibrium, Einstein says she isn't sure. "This is a big open question. We do know that hormones are very complex and act on every single body system." Lab experiments have shown that estrogen affects single neurons in the brain, she says, but how that specifically pertains to mood or behavior is still a mystery.

It feels dangerous to complain about the Pill when retro-minded legislators in every state and most branches of the federal government are determined to chip away at women's right to choose, and 49 percent of our nation's pregnancies are unplanned. After all, in June 2013 Wisconsin's state assembly passed a bill limiting women's access to contraception (the fate of the bill lay in the hands of the state senate at press time), and the FDA tried to make the morning-after pill available only to women over age 15, despite a federal judge's ruling—and this was at the behest of the relatively liberal Obama administration. "The Pill and contraception in general have become so tied to our conversation about abortion that it's really difficult to talk about honestly," says Laura Eldridge, author of In Our Control: The Complete Guide to Contraceptive Choices for Women. "It feels like giving fodder to the other side. I understand those anxieties, but it's not in the service of women to avoid talking about these realities." Eldridge says she's been asked to speak to anti-choice organizations eager to scare girls away from contraception altogether. "Any criticism of birth control has been co-opted completely by people with a very antiwoman, antisex agenda," Grigg-Spall adds. "And that's partly the fault of the women's movement. We've let [the right] take control of the conversation."

Instead, these advocates say that women need to be talking more openly about the drawbacks of the Pill as a cure-all—so we can push doctors, researchers, and the pharmaceutical industry to give us better options. Because right now, they're pretty limited. On the contraception front, IUDs are gaining ground, but fewer and fewer doctors are prescribing basic yet effective methods like the diaphragm or condoms. The "fertility awareness method," once the sole province of religions that didn't allow other forms of contraception, has been newly embraced by holistic women's health experts such as Northrup, who says it can be at least 95 percent effective when used correctly. She says, however, this requires that "women interact consciously with their fertility, and the reality is that many women still don't have conscious dominion over their fertility. Or they're just too busy. There are times in many women's lives when it makes sense to put your pelvis on autopilot."

For other problems, the list of alternatives is even shorter. To treat endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and hormonal infertility, Prior likes to use a naturally derived progesterone, called Prometrium, because it doesn't get metabolized into estrogen in the same way that synthetic progestins do. But so far her strategy hasn't caught on among her fellow physicians. Prior and Northrup both encourage women to explore how diet, exercise, stress, and other lifestyle factors impact their reproductive health.

But when I asked my surgeon about such approaches for my endometriosis, he shrugged and said, "We have no idea whether any of that makes a difference." A classic and infuriating surgeon's response, yes—but I'm here to say that when you're living in pain, you don't want to hear how maybe giving up refined sugar or doing more yoga will make things better in three months. You want a pill that makes you feel better. Now.

There's the rub. We still want the convenience, freedom, and empowerment that the Pill delivered when it hit the market in 1960. And it does have some serious upsides: Few things beat the Pill for pregnancy prevention, and it substantially reduces a woman's chances of getting very lethal cancers like endometrial and ovarian cancer (however, some studies have shown the Pill may raise the risk of breast cancer while women are taking it and for up to 10 years after they stop).

None of the Pill critics I interviewed wanted to limit a woman's access to the drug if she is happy with it. "The Pill works very well for many, many women," Eldridge says. It's the rest of us, however, who could use a little more attention from mainstream medicine.

As for me, I'm still on hiatus from the Pill, for an unexpectedly cheerful reason: Despite my endometriosis, I got pregnant last year, and my pregnancy and, now, breast-feeding appear to be doing what neither surgery nor the Pill could—my cysts and lesions have disappeared, as has my chronic pain. If the disease doesn't recur, I'd like to stay away from synthetic hormones, especially since I get the occasional aura migraine, which means I have a higher risk for blood clots and stroke. If the endometriosis returns, however, a daily piece of duct tape on the dashboard light may be my best option.

Via elle.com.

Photo: Getty Images

Virginia Sole-Smith is the author of The Eating Instinct: Food Culture, Body Image and Guilt in America, and writes the newsletter Burnt Toast.