The other night, I went out to dinner by myself to Fish La Boissonnerie, a seafood place just around the cobblestoned corner from my new apartment in the Sixth Arrondissement of Paris. I sat at the counter, ordered a glass of red, and befriended the American woman next to me. She asked why I'm here.

"I was sick," I replied. And that was that.

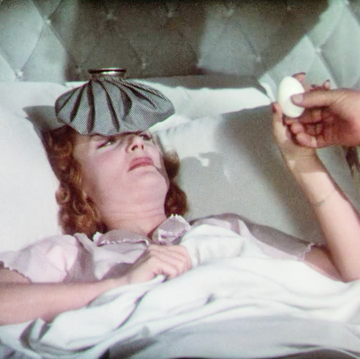

Maybe sick is an understatement. I've been through a special circle of hell consisting of six rounds of chemotherapy, two surgeries, three transfusions, one stay in isolation, and more shots than I can count. My oncologist called the treatment regimen "spicy." (Really, it's ghost-pepper levels of scalding.) The whole time, I just wanted to go back to normal, a normal day in which nothing bad happened and I didn't feel like total shit.

After I finished chemo and got a clean bill of health in April 2015, I got what I wanted … sort of. I'd been so consumed with wanting everything to be the same again that I didn't realize what had changed in the meantime: me. I could no longer figure out where I fit in my own damn life.

I spent months trying to contort myself into my old routine. Wake up early, run, walk to the office, eat a tuna sandwich, work some more, go home, cook dinner, watch TV, go to bed.

My biggest adjustment was trading Grey's Anatomy for Mr. Robot. I tried hard to shoehorn my new self into my old life — after all, I'm the one who wanted it. But I began to question my place: at my dream job as a beauty editor at Cosmo, in a cozy apartment crammed with my favorite books and a view of the East River and, beyond that, Queens.

For a lot of people, moving to New York City after college is a daring leap. For me, it was a statement of the obvious. With a good pair of binoculars, I could practically see from my living room my mom's old neighborhood, the house in which my dad grew up, and the Chinese restaurant we went to every single weekend. Since returning home after graduation, I'd done everything I was supposed to: get an apartment, get a job, climb the ladder, and find some satisfaction from it.

But in the months after treatment, I began to feel trapped in my own comfort zone, like I was in a fishbowl, doomed to swim through the same miniature shipwreck and plastic seaweed until the end of my days. I'd never strayed from the status quo. I'd never lived abroad. I'd never traveled alone. My idea of a risk was calling the cable company and bluffing about canceling in order to get a lower rate. I'd stuck to the straight and narrow, and I had never been more lost.

I didn't know how to fix myself or my situation. I'd become so accustomed to everyone giving me orders, telling me the right course of action. As a patient, I had no control. Even before chemo, the fertility nurses left daily voicemails telling me which hormones I needed to inject and when. My oncologist's office scheduled my checkups and treatment, and then sometimes changed dates without asking me.

The entire time, I spoke up for only a single thing. When scans came back showing how effective the chemo had been (which, luckily, was very), I called an oncologist on my case and asked her to please let me stop at five rounds of chemo instead of six.

"No, I'm sorry," she answered firmly. "You have to do six."

"OK," I said. "But I looked it up, and the literature for this actually recommends four to six rounds."

"Deanna, that literature? I wrote it."

Six it was. There's no compromising when you have cancer. I had no control over what was happening to me and my life and my body. It's the reason that nothing drives me more batshit than when people, even with the best intentions, call me an inspiration or a warrior or some other empty word that implies I even did a thing. I think "cancer witness" is more appropriate. I watched it happen. I saw the abnormal numbers in my blood work. I read my scan report: tumors, two, maybe three. I watched the chemo nurse push the vincristine into my IV. I didn't fight. I didn't battle. I just sat under warm blankets and tried to swallow the vomit. My body was just a vessel for this happening, this squashing of a mutiny launched by some cells with a god complex.

A few months ago, in an effort to divert the conversation from his love life (status: in shambles), a friend asked me, "What scared the shit out of you when you were going through treatment?"

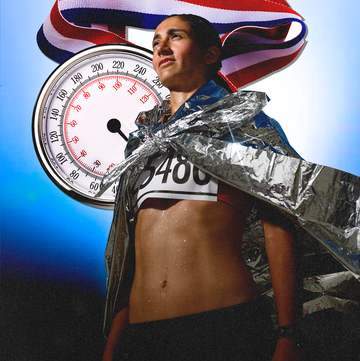

What scared me is how easy it is to die. You're lucky if you get advance notice. I was 23, never sick (unless you counted hangovers), with big plans for a half marathon, for kids, for a house, for traveling. When you're young and invincible and the world is your oyster and you're finally getting your shit together, life seems deliciously long, like it's the second day of vacay and you still have five days left on the beach. There's time to spare, time to retire and do what you actually want, time to postpone the "one day" and the "someday."

I realized while maybe dying that time is an excellent con artist. You can't count on it. I'd been building my life around the assumption that I had time. But really, I'm just borrowing it on tenuous terms. Death is waiting to pull the rug out from under all of us.

There's no shame in routine. A steady paycheck and a weekly brunch count for a lot. But I don't have time to settle. I've been sick not once now but twice. On top of my increased risks of leukemia and heart failure (ironically, side effects of chemo), a new study published in the journal Cancer shows that nearly 14 percent of young-adult survivors will get another, totally different kind of cancer. History has shown that the odds are not in my favor. How many times do I need to get cancer before I finally do something for myself?

So in September, I did what I've always wanted to do and booked a flight to Paris. At this, my boyfriend, Tim, smiled and shrugged. We see each other mostly on weekends, so stretching out the time between visits isn't a big deal for us: He gets that I want to do this by myself. (Anyway, I think he's secretly pleased that he can watch hockey with his friends every weekend.)

I found an apartment down the block from the Seine. I quit my job, finding myself unemployed for the first time ever. I felt giddy and nervous, like it was my birthday, Christmas, and the apocalypse all at once. I put down the security deposit on my apartment and skipped around my studio, yelling, "Au revoir, mes petits choux! Je pars, bitches!" I am getting the eff out of here. I'm going to speak French again, something I learned in school and promptly forgot. Where do I go? What do I do? How do I spend my time? Who knows! I'll figure it out.

These days, in my tiny apartment with huge windows and a view of the Pont Neuf, I have no routine at all. Sometimes, I get really crazy and don't set an alarm. I consider whether I want a croissant or to cook eggs to top the fresh sourdough that I pick up at the boulangerie, because that's now an option. I run either through the Luxembourg Gardens or to the Eiffel Tower and back. I write. I read outside beside my l'apéritif, or I sit inside and chat with the bartender. I meet friends of friends over plates of garlicky escargot (or even better, unlimited French fries). Most often, I go for a walk — to the market, to the crêperie on rue Saint-André des Arts, to a café where I can sit and people watch — and end up somewhere new.

This aimlessness is everything. I have no appointments. I have no one telling me where to go and when to be there. And I'm no longer trapped in the confines of the small, regimented life that took up so much of my time but gave me little in return. Even after November's horrifying terror attacks — during which I was lucky to be on the other side of the Seine, a mile or two away — Paris is about joy and life. Watching its people in the aftermath is like taking an immersive crash course in hopeful celebration in the face of suffering and anxiety, something that doesn't come naturally to me. I am learning.

What has become very clear is that nothing really matters unless it matters. I know that this sounds like a tautology, and it probably is. I hate tautologies (tell me "You do you" and I'll hang up and block your number). But what I mean is: Unless something matters to me, it doesn't matter. Here is the feeling of relief I've been searching for since April. Here is the sigh. Here it is, at a small round table in a bistro on a gray, drizzly day in Paris.

Lately, all I think about is a line from a T. S. Eliot poem: "The end is where we start from." I've ended my cancer-riddled life in New York. When my luck runs dry and my time ticks down to the last seconds, at least I'll know that I did it. I took matters into my own hands and made this a life worth saving.

This article was originally published as "I Had Cancer and It Changed Everything" in the February 2016 issue of Cosmopolitan.